S Gopalakrishnan

Research Intern,

Jindal Centre for the Global South,

O.P. Jindal Global University, India

Email: 23jsia-sgopalakrishnan@jgu.edu.in

Introduction

In its G20 presidency, India prioritized being the Voice of the Global South and raised its concerns. According to this goal, it seems essential to understand the Global South and the challenges each country faces in its path to development. In this article, I take up the challenges faced by Sri Lanka, especially because of its deep friendship with India and its neighbor. Besides, the economic crisis of Sri Lanka is of interest to us as we can see an interplay of factors that affect the political systems of the Global South countries. In today’s era of multipolarity, where the world needs additional alternatives, as the ORF President Dr Samir Saran opines, it becomes necessary to understand what Global South is and where Sri Lanka fits in the global paradigm.

This article endeavours to explain how political structures impact economic progress, focusing on Sri Lanka.

What is Global South?

While the ‘Global South’ refers to those countries that are developing in terms of economics, the real point of difference, as Samuel Huntington believes, is that these countries generally have ‘Non-Western’ cultures or that their civilisation has such characteristics that are distinctly not ‘West’. In his book (Clash of Civilizations, 1996), Samuel Huntington pointed out the real category to distinguish this so-called ‘Global North’ and ‘Global South’. He says, “…the most common division, which appears under various names, is between rich (modern, developed) countries and poor (traditional, undeveloped, or developing) countries. Historically correlating with this economic division is the cultural division between West and East, where the emphasis is less on differences in economic well-being and more on differences in underlying philosophy, values, and way of life…”.

This ‘underlying philosophy, values, way of life’ governs the political systems of the nation-states. Politics, not economics, distinguishes the ‘Global South’ states from the ‘Global North’. Huntington notices that while rich states fight trade wars with each other, poor states fight violent wars with each other. Perhaps this is the reason why violent conflicts are becoming common in the Global South countries like South Sudan, Israel, Palestine, India, Pakistan and many more. The main elements of such violent conflicts, such as recent crises like the Economic Crisis of Sri Lanka, Israel – Hamas, and the Taliban Government in Afghanistan, are human rights violations, territory, politics of ideology and identity, and power.

The latter half of the twentieth century saw how the now independent countries tried to achieve economic competence like the West. While experimenting with policies under ideologies of capitalism and communism, the countries were exposed to violent conflicts. Since then, violent political conflicts and economic development formed a direct relationship (Abeyratne, 2004).

Sri Lankan Political Science

The Economic-Political Landscape of Sri Lanka is an interplay of ethnic, ideological, and economic factors. These factors were not new; they had been at play since Independence.

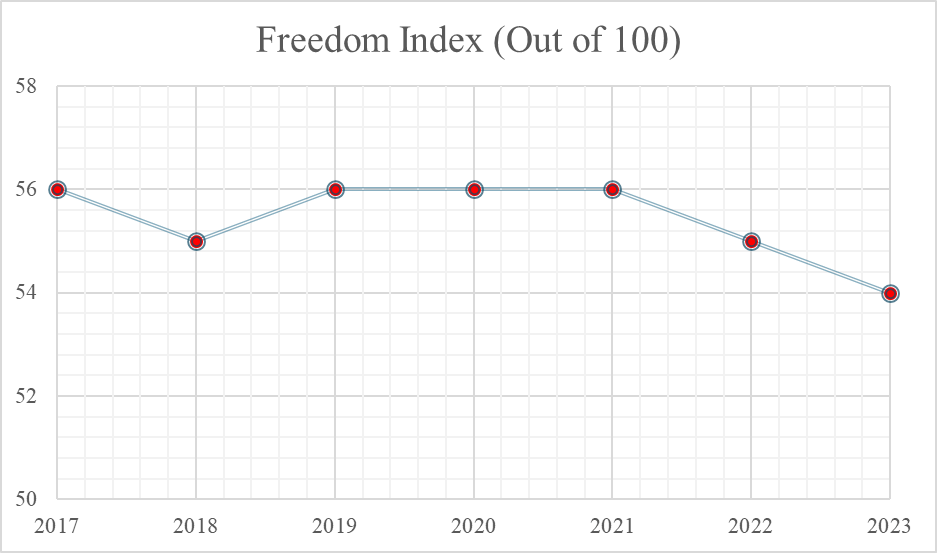

The above graph illustrates that in seven years till 2023, Sri Lanka has been designated as partly free (Abramowitz, June 21, 2023). The country seems seemingly stable in these seven years, ranging between 56 and 55, despite the pandemic in 2019 and 2020. The index dipped in 2022, which was the year when the economic and political crisis became severe. Although it seems the country is still recuperating the previous year, the index dipped further. Based on the graph, the lowest was in 2023.

The graph can also be viewed based on regimes. The years can be divided into two sets: the years of Maithripala Sirisena administration (2017-19) and the years of Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration (2020-23). Based on ideologies, the Maithripala Sirisena administration, belonging to the Sri Lanka Freedom Party, was center-left, while the Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration was right-leaning. Viewed from this paradigm, it seems the freedom index dipped more during the latter regime. This shows that Sri Lanka was ‘less free’ under the Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s administration.

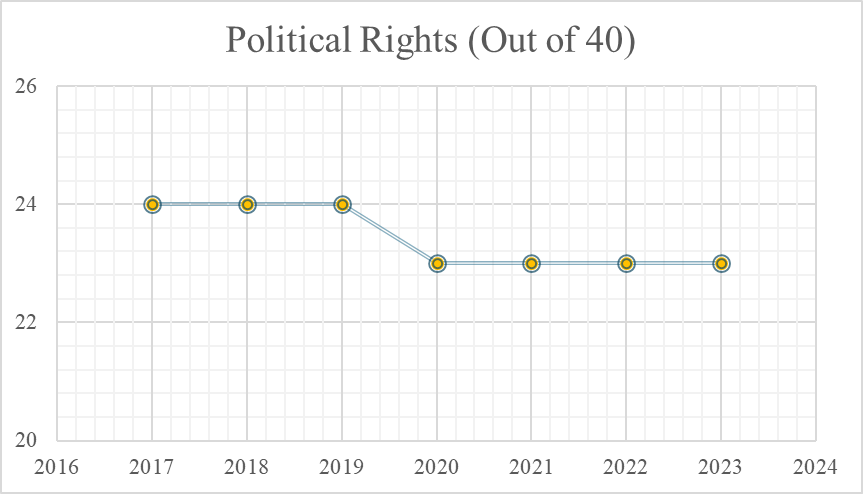

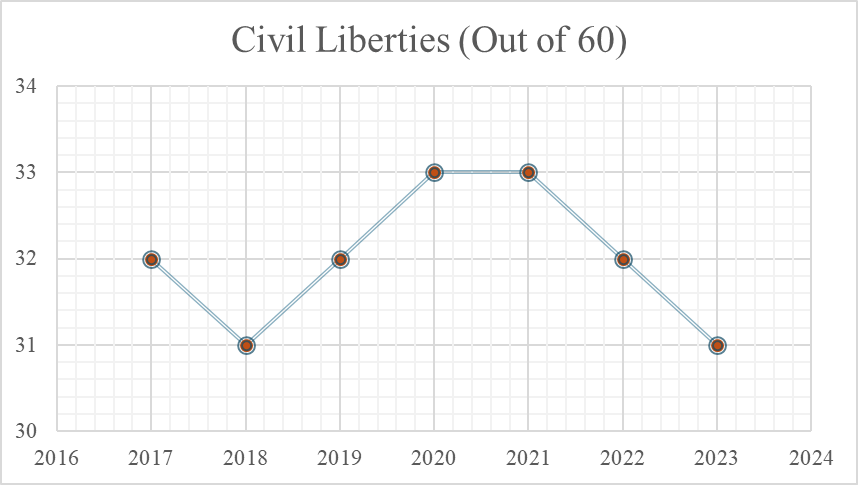

The graphs below further elaborate on the minute differences between the two regimes related to respect for political rights and civil liberties.

Regarding political rights, the Maithripala Sirisena administration gave more freedom to express political opinions compared to the Rajapaksa administration. However, it seems in the case of civil liberties, there is no clear winner. Both administrations experienced the lowest drop in giving freedom to civil liberties.

From the above analyses, it is clear that there are minute political differences (not ideology, but political practice) between centre-left and right-leaning regimes. Yet, both did not ensure a completely stable political environment in Sri Lanka (the highest score for these indices as per the NGO is 97 or 98). The Maithripala Sirisena Government experienced constitutional crises when the President attempted to remove Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe from the post and appoint Mahinda Rajapaksa instead. This led to political disagreements and power struggles (Abramowitz, June 21, 2023). Thus, when it comes to politics in Sri Lanka, it is the government’s actions and not the ideologies that must matter when it comes to understanding the political instability in the region.

Relationship between Politics and Economics of Sri Lanka

This section aims not just to elaborate on how Sri Lanka fares in escaping from political, violent conflicts to economic development but also to understand what sorts of development processes and patterns cause such conflicts.

The economy of Sri Lanka seems to be an example of a ‘potential case in development success’ (Abeyratne, 2004). According to Joan Robinson, Sri Lanka’s per capita income was one of the highest in Asia at the time of Independence. The economy was rural and accounted for 37% of the GDP. It accounted for 88% of the export earnings and 27% of the employment. This seems to be the backbone of the economy. In a research paper by Prof. Sirimal Abeyratne of the University of Colombo, the political and economic aspects of Sri Lanka are compared with the likes of Malaysia. While Malaysia succeeded, Sri Lanka succumbed to the conflicts. The question is, why is it so?

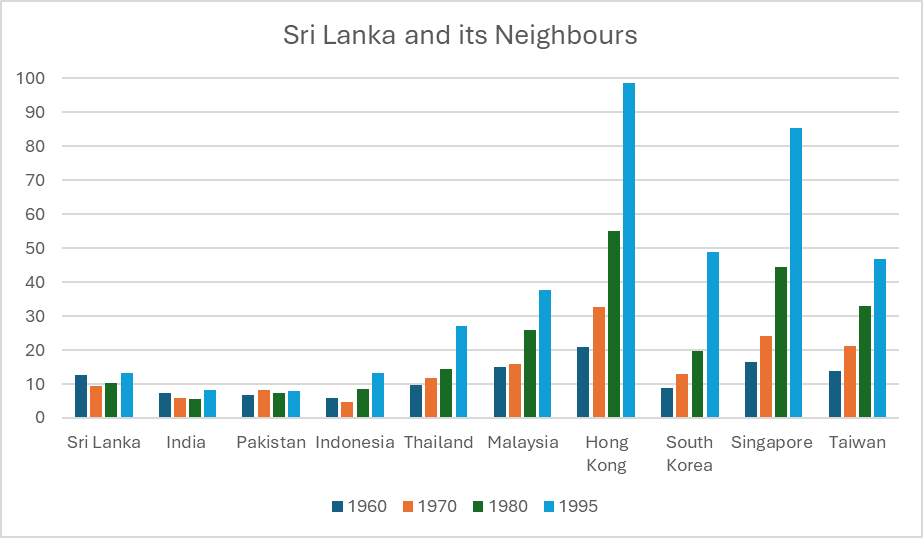

The graph below illustrates the economy (based on per capita GNP relative to USA) of Sri Lanka and other global south states from 1960 to 1995:

The above graph gives a bird’s eye view of the progress made by these countries over the years (Hong Kong is a special administrative region). It is clear from the chart that Sri Lanka has not achieved much economic progress. Sri Lanka also experienced political conflicts in the form of Tamil-separatist movements in the North and the youth in the South in the 1970s, which led to an ethnic conflict and civil war in the 1980s.

Today, Sri Lanka’s political atmosphere and structure differ greatly from the other ‘Global South’ nations. It is a mixture of Presidential and Parliamentary forms of Government with a unitarian touch. Despite frequent slipbacks to authoritarianism, Sri Lanka can be seen as a partly Liberal Democratic State. In a Liberal Democratic State, the political system has three principal actors: the State, the People, and the Civil Society (KK Ghai, 2022). These actors’ optimum efficiency and coordination ensure the vitality of democratic values. Most of the Global South states succumbing to authoritarian or totalitarian waves, like Pakistan, Myanmar, and Afghanistan, experience inefficiency in terms of the people and civil society participation and the dominant power of the state, mostly the ruling elite. However, in the case of Sri Lanka, the power dynamic seems to be the opposite; the people and civil society are strong, but the state is weak. The people are struggling to consolidate the democratic traditions of a Liberal Democratic State.

Conclusion

In this scenario, there is a silver lining. In an article, a senior researcher and lawyer with the Centre for Policy Alternatives based in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Bhavani Fonseka, said, “Despite troubling trends of authoritarianism, democratic backsliding, and ethnomajoritarianism (ethnic majority dominating the minorities in determining the future of the state and society) sweeping across Sri Lanka, key moments in recent history have united diverse groups in a show of peaceful pushback. These events have enabled the most recent wave of citizen mobilisation, which can potentially transform Sri Lanka significantly.” (Fonseka B, June 30, 2022)

The route to democracy may be long and hard, but if the people remain politically conscious and active, the ruling elite will ultimately be responsive and accountable out of compulsion. This is the hope for the nation.

References:

- Huntington, S. P. (2016). The Clash of Civilisations and the Remaking of World Order (4th ed., p. 33). Penguin Books. https://www.google.co.in/books/edition/The_Clash_of_Civilizations_and_the_Remak/Iq75qmi3Og8C?hl=en&gbpv=1

- Abeyratne, S. (2004). Economic Roots of Political Conflict: The Case of Sri Lanka [Research Paper, University of Colombo]. https://crawford.anu.edu.au/acde/asarc/pdf/papers/2002/WP2002_03.pdf

- Abramowitz, M. J. (2023, June 21). Sri Lanka: Freedom in the World 2023. Freedom House. Retrieved January 2, 2024, from https://freedomhouse.org/country/sri-lanka/freedom-world/2023.

- Ghai, K. (2022). ISC Political Science: Political Theory and Contemporary International Relations, Class XI. Kalyani Publishers. https://www.flipkart.com/isc-political-science-theory-contemporary-international-relations-class-xi/p/itm79e7d4d115a76

- Fonseka, B. (2022, June 30). Sri Lanka’s Crisis and the Power of Citizen Mobilization. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/06/30/sri-lanka-s-crisis-and-power-of-citizen-mobilization-pub-87416

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author (s). They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Jindal Centre for the Global South or its members.