Swapneel Thakur

E-mail: 20jsia-sthakur@jgu.edu.in

M.A. (D.L.B.), Jindal School of International affairs, O.P. Jindal Global University

Abstract

The principal purpose of this research is to determine the kind of change that the COVID-19 pandemic might bring with, either the possibility of countries resorting to trade practices that are protectionist in nature to safeguard domestic interests or a complete change in structure of international trade that affects all. The design of this research is based on India’s setback due to the pandemic in international trade and its way of tackling this. Although India looks to counter the pandemic using export and domestic production policy, it is not likely to become protectionist. However, if these policies are successfully implemented, the desired result would be a lot better than just a boost to international trade, as it would lead to the formation of a completely new system.

Keywords:

Pandemic, global supply chain, self-reliant, exports, imports, domestic, manufacture.

Introduction

The COVID-19 Pandemic has been the most unexpected and, one of the worst hitting pandemics since the Spanish Flu in 1918. Even after the gift of advance scientific knowledge, the pandemic does not seem to slow its pace. Although countries seem to look towards a more adaptive response, our only hope lies in the proposed vaccines. While the pandemic is set to leave a lasting effect on daily lives and the idea of a “new normal”, it certainly did not spare the global economy. The pandemic hit so fast that countries did not have time to put effective measures in controlling the spread of the virus. In the immediate need of a strategy, measures such as complete lockdown and temporary closure of non-essential manufacturing facilities were taken. This in turn took a huge toll on travel and supply chain management which then resulted in a steep fall in global trade. This economic recession was not just destructive but a spill over because of the shock that the demand and supply market chain faced due to constraints in movement. This shortage in supply led to inflation of prices in remaining products, especially basic commodities (Ozili & Arun, 2020, pp. 9).

With States focussing on a phase-wise unlock, there has been significant effort in restoring the broken supply chain, but the experience of a global disruption of the supply chain has forced countries to rely on their domestic production. Now, when the supply chain is on its way to becoming fully functional, there lies a possibility that it would harm domestic production as well. This paper aims to deduce if the response to this condition leads us to an era of protectionism or would this be a paradigm shift of the international trade system. With the constant change in international order through consensus building between nations and multilateral organisations such as the World Trade Organisation, World Bank and International Monetary Fund, protectionism, as an economic practice has seen a sharp decline in the international trade system. States have forgone their traditional economic practices and embraced an approach towards having more liberal trade policies. Although it is easy for a protectionist economy to become a liberal economy, it is very tough to do the opposite. But amidst the factor of international accountability there is now seems an emergence of both a mixture of protectionist and liberal trade systems.

Lukasz Gruszczynsk through his article The COVID-19 Pandemic and International Trade: Temporary Turbulence or Paradigm Shift? Looks to solve the same question in a very different way. He assesses both the short-term and long-term consequences of the pandemic and concludes that although the pandemic is devastating, recovery to a normal international trade system is still manageable. However, if the virus stays a bit longer then there could be a possibility of a paradigm shift. Raj Bhalain his article Covid-19 And The New ‘Healthy Trade’ Paradigm for Bloomberg looks to answer this question from the perspective of creating a better trade system. He puts forth solutions to the possible rise of problems in the international trade system such as the rise of protective measures, export restraints, and subsidies.

Thus, my aim in writing this paper seeks to answer from the perspective of India and its policy:

- What could be the trigger point for a change in the international trade system?

- Can protectionism still sustain in this era of liberalisation?

- If not, what should we consider as a paradigm shift in the international trade system?

Protectionism or A Paradigm Shift?

Lukasz Gruszczynsk’sThe COVID-19 Pandemic and International Trade: Temporary Turbulence or Paradigm Shift? develops the argument by dividing the consequences based on the time till which it might be in effect. He classifies sectors such as tourism, air travel and container shipping as short-term consequences of the pandemic. He also looks to classify temporary export restrictions on medicines and food, and a shrinkage in the flow of Foreign Direct Investments as just short-term consequences which could be cured in a given time. However, he argued that long-term consequences could be the change in the structure of the global supply chain. He takes the example of China being the global dominator for pharmaceutical goods and that now with the advent of the virus, countries like the US could look to challenge China and restructure the global supply chain. Raj Bhala in his article Covid-19 And The New ‘Healthy Trade’ Paradigm for the Bloomberg has a more straight-up opinion and looks to believe that the pandemic could create a healthier international trade system. His answer to all the problems that the pandemic has pointed out was to re-examine and re-structure existing policies and frameworks. His final conclusion looks to advise that instead of waiting for the pandemic to end, a healthier system would be to work against the pandemic.

Yet, the pandemic has defied all possible predictions of its end with cases still on a rise. This is why our idea of the consequences of international trade needs to be re-structured. The essay aims to look at three different time frames which are the pre-pandemic, lockdown and unlock. It is through understanding the kind of policies that existed pre-pandemic, policies taken during the lockdown and their implications on policies in the subsequent unlock, can we conclude on the question at hand.

Pre-Pandemic:

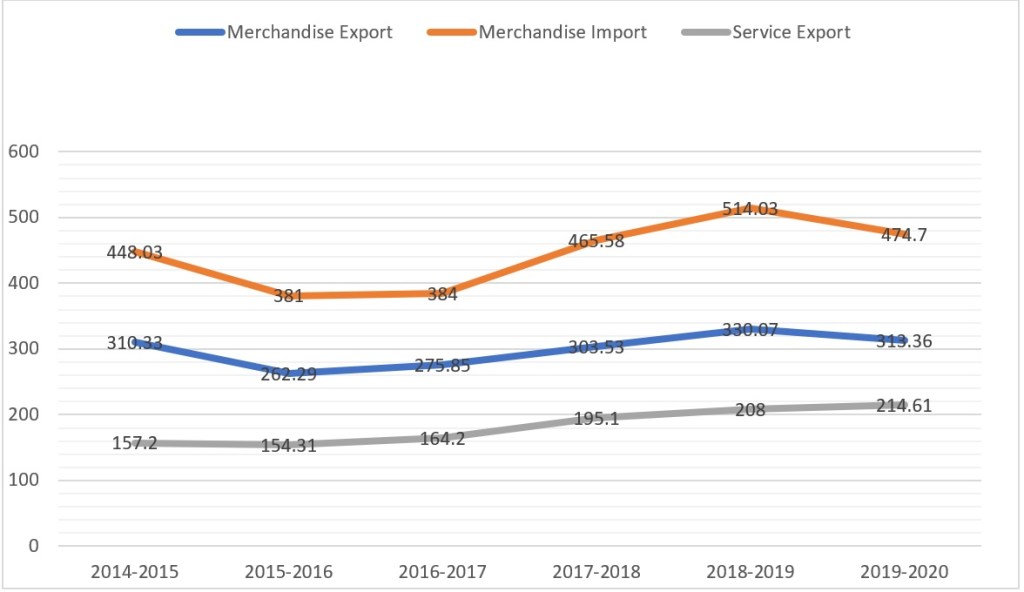

In 2015, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry had brought about a new International trade Policy which was to be in effect from 2015-2020 (Government of India, 2015). The new policy had two export schemes which were the Merchandise Exports from India Scheme (MEIS) and the Service Exports from India Scheme (SEIS). Thus, aiming towards a more export-oriented international trade.It also aimed to increase India’s exports of merchandise and services from $ 465.9 billion in 2013-14 to approximately $900 billion by 2019-2020 and to raise the Indian share in world exports from 2 percent to 3.5 percent (Sharma, 2019, pp. 116). Further, this policy also acted as a compliment to domestic policies such as Make in India and Skills India which look to create businesses, encourage entrepreneurship and employment, in light of the high youth percentage in the country. Table 1 below, shows the net exports from 2014 – 2019 and Table 2 below, shows the net imports for 2014-2019. On a closer analysis, we find that exports and imports have shown an increase from 2014 to 2019 along with trade deficit as imports have also shown significant growth during this period. Although oil has always been a major import for the country, another possible reason behind this deficit has been the rise in import of consumer products like electronic goods and stones, and intermediate goods such as machinery, inorganic and organic materials in a country with a rising middle class and budding entrepreneurial minds (Government of India, 2019) However, the export composition has seen a gradual shift from agricultural to non agricultural commodities (Trade Promotion Council of India, 2018). It has seen a rise in export of engineering, luxury and pharmaceutical products (Government of India, 2019). The graph also reveals that India has maintained trade surplus in terms of services. Covering a wide variety of activities such as from hotels and restaurants to business services, India has shown an increasing trend in service exports which are majorly destined to USA, UK and Japan.

Lockdown

When the pandemic first hit India, a nationwide lockdown was implemented by the Ministry of Home Affairs for a period of 21 days, which started on 25.03.2020 was scheduled to end on 14.04.2020 but the uncontrollable spread of the virus resulted in another lockdown which was for 19 days that ended on 03.05.2020. Although the Foreign Trade Policy was extended for the year right before the lockdown, suspension of working for the manufacturing industry of non-essential items and the services industry, and ban in international movement resulted in a sharp decline in merchandise export and service export. Further directives issued by the government, banned the export of pandemic essential supplies to other countries, to preserve the stock. Exports of clothing, masks, gloves used to protect wearer from airborne particles, and any other respiratory masks were suspended with certain exceptions while the export of medical equipment such as ventilators were banned fully (Elias, 2020). The Directorate of General of Foreign Trade also restricted the export of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients such as paracetamol, tinidazole, chloramphenicol, and 23 other drugs, sanitizers and diagnostic kits and their agents during this time (Elias, 2020). Thus, this resulted in a sharp decline of 61% in merchandise exports, while the lockdowns in other countries resulted in a decrease in imports by 60% and a decline of 8% in export and 18% in import when the virus was at its worst in April. Given below Table 3 and Table 4 show the month-wise statistic of both export and import of Merchandises respectively and Table 5 and Table 6 show the month-wise statistic of both export and import of Services during the lockdown period with reference to the previous year.

Unlock

With provision lockdowns from 4.05.2020 to 30.05.2020, the Ministry of Home Affairs announced their series of relaxations on the current lockdown as a policy of phase wise reopening of the nation. These relaxations came to be known as Unlocks that allowed the reopening of shopping malls, theatres, religious, social, and sports events, offices and, manufacturing, international travel, and distribution of non-essential items and services. Further, the ban on exports of masks, PPE kits, and other protective gear were lifted with an export quota of 5 Million a month. This helped in reviving the export market in India which was ready to manufacture immediate COVID-19 protection gears, essential goods, and non-essential goods and services in the gradual lifting of lockdown in other countries which needed. These gradually lifting lockdown countries were now also prepared to export their commodities such as telecom equipments, gold, and petroleum which India is in need of. The monthly statistics for both import and export can be seen in Table 7 and Table 8 respectively.

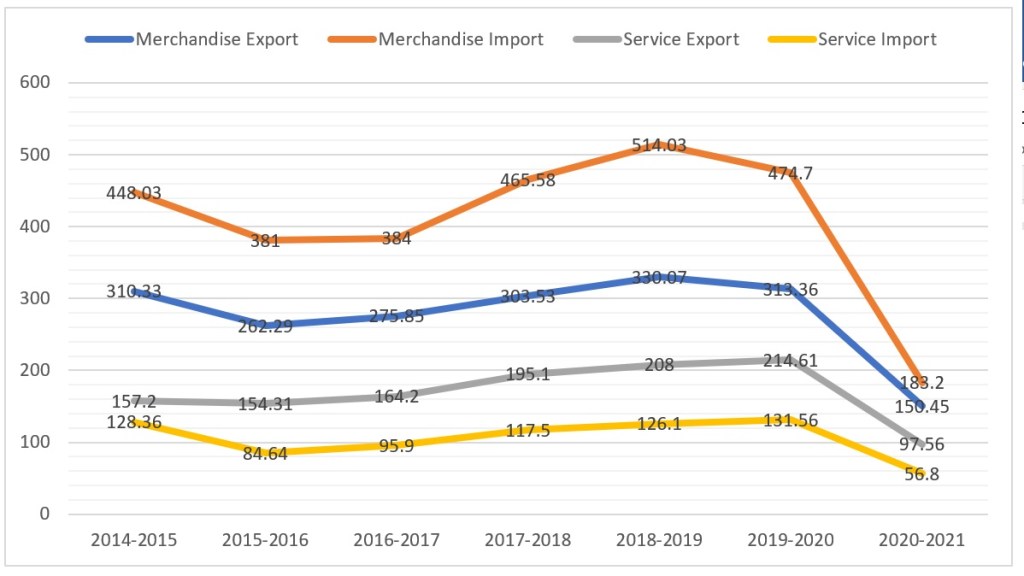

However, this does not take away the fact that India’s international trade, took a severe hit. If we look at graph 2, there is a steep decline in merchandise import. Although this is bad, a positive side of it is that decrease in imports of goods, because of the pandemic, creates a great opportunity for domestic manufactures and service providers to enter the market as suitable alternatives and thus, capitalising on this situation to their profit. For a country with a high work force and young minds with entrepreneurial capabilities, this becomes a perfect business opportunity, and thus to cater to it, the Government of India launched its campaign to revive the economy, the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan or Self-Reliant India Mission (The Indian Express, 2020). With policies such as Make in India, still existing and policymakers promoting slogans such as “Vocal for Local”, domestic manufacturers will have better opportunities to attract consumers and come to light. India also used a part of its famous “20 Lakh Crore Package” to boost MSMEs in light of its campaign.

With the race for a vaccine almost coming to an end, it is likely that things would start going back to normal within another 2 years and pandemic although not completely but majorly gone. This could re-establish the broken supply chain management and thus, increase foreign imports again in the country. This might severely affect domestic manufacturers and entrepreneurs who would have to compete with known brands in this rising country of a middle-class standard of living and further become contrary to the idea of self-reliance. This brings the question of whether India would respond with a protectionist policy to protect its domestic manufactures and loss of employment.

| Exports | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | 2017-2018 | 2018-2019 | 2019-2020 |

| Merchandise (USD Billions) | 310.33 | 262.29 | 275.85 | 303.53 | 330.07 | 313.36 |

| Services (USD Billions) | 157.20 | 154.31 | 164.20 | 195.10 | 208 | 214.61 |

(Sources – Ministry of Commerce and Industry, 2020)

| Imports | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | 2017-2018 | 2018-2019 | 2019-2020 |

| Merchandise (USD Billions) | 448.03 | 381 | 384.36 | 465.58 | 514.03 | 474.70 |

| Services(USD Billions) | 128.36 | 84.64 | 95.90 | 117.50 | 126.10 | 131.56 |

(Sources – Ministry of Commerce and Industry, 2020)

Graph 1–Graphical representation of Indian exports and imports

| Merchandise Exports | |||

| Month | 2020 (USD Billions) | 2019 (USD Billions) | Decline (%) |

| April | 10.16 | 26.03 | -61 |

| May | 19.23 | 55.88 | -47 |

(Sources – Ministry of Commerce and Industry, 2020)

| Merchandise Imports | |||

| Month | 2020 (USD Billions) | 2019 (USD Billions) | Decline (%) |

| April | 17.08 | 42.39 | -60 |

| May | 22.85 | 46.68 | -55 |

(Sources – Ministry of Commerce and Industry, 2020)

| Service Exports | |||

| Month | 2020 (USD Billions) | 2019 (USD Billions) | Decline (%) |

| April | 16.45 | 18.06 | -8 |

| May | 16.76 | 18.68 | -10 |

(Sources – Ministry of Commerce and Industry, 2020)

| Service Imports | |||

| Month | 2020 (USD Billions) | 2019 (USD Billions) | Decline (%) |

| April | 9.30 | 11.40 | -18 |

| May | 9.93 | 12.49 | -24 |

(Sources – Ministry of Commerce and Industry, 2020)

| Export | ||

| Month | Merchandise | Services |

| June | 22.01 | 16.99 |

| July | 23.74 | 17.03 |

| August | 22.83 | 16.44 |

| September | 27.85 | 17.29 |

(Sources – Ministry of Commerce and Industry, 2020)

| Import | ||

| Month | Merchandise | Services |

| June | 21.32 | 9.96 |

| July | 28.48 | 10.05 |

| August | 29.52 | 9.60 |

| September | 30.34 | 10.14 |

(Sources – Ministry of Commerce and Industry, 2020)

Graph 2 – Change in Net trade from 2014 to 2020

Conclusion

The idea of India starting a protectionist era with its aim of self-reliance is highly unlikely. Theoretically, if India looks to maintain its position and aim as one of the biggest global exporters, its demography makes it tough to maintain a protectionist economy. India is the 2nd most populated country in the world and is set to take over the position of 1st occupied by China in the upcoming years. A protectionist policy in this case would result in high demand and low supply in the 21st century. It is also because of its demographics; some economists perceive India as a labour-intensive country and not capital intensive and thus it wouldn’t be possible for entrepreneurs to cater to all. One might argue that why China as the world’s most populated country become a hub for capital-intensive manufacturing. This is only because the country’s development in statistical, telecommunications, office, and consumer electronic equipment sectors makes it a perfect capital-intensive manufacturing hub (Qureshi and Wan, 2008, pp. 5). Judging by its position in international politics, organisations such as WTO and regional economic organisations such as SAARC and Shanghai Cooperation restrict it from becoming completely protectionist.

However, if India should succeed in achieving self-reliance and a top position as a global exporter, then it is likely that it would pose a paradigm shift towards a change in the global supply chain system. COVID-19 has forced countries to rethink the current system of the global supply chain. Suppliers such as Foxconn and game giants such as Nintendo, have now reconsidered their supply chain system in China (Mint, 2020). Further, the severe backlash due to the mishandling and spread of misinformation of COVID-19 has resulted in the prohibition of HUAWEI’s 5G initiative, while India looks to implement 5G with Reliance Jio in the second half of 2021. Most importantly, with the race for a vaccine almost coming towards an end, India looks to become one of the key manufacturers of vaccines which will significantly change the global chain value system of vaccines. Thus, if India succeeds in becoming a self-reliant economy, it could pose a paradigm shift to the existing international trade system.

But there is a long way to go for India to achieve a self-reliant economy. With a total of 9800000+ confirmed cases and 350000+ active cases until the month of December (Government of India, 2020), India is the 2nd worst country to be effected by the COVID-19 pandemic. Its new farm bills which looked to provide direct transactional opportunity between farmers and corporates, which was one of the steps under the banner of Atmanirbhar Bharat, are still facing significant opposition from its citizens and especially farmers. Further, China’s attempt to provide a vaccine successfully might also mend relations lost due to the pandemic. Both Sinopharm and CanSino Biologics might prove to become successful contributors in this fight against the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, its aggressive domestic and foreign policy has led to a negative impact on its long-standing supporters such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Russia. With the change in leadership of its strongest ally, the United States, there still exists ambiguity on the kind of relations it might share as Prime Minister Modi was vocal about Trump’s re-election with the slogans such as “Ab ki bar Trump Sarkaar” (This time again, Trump’s Government). Thus, there also exists possibilities in India not completely creating a paradigm shift.

A way forward?

India needs to significantly change its current foreign policy to produce an effect on its way to changing the paradigm. Traditional BJP Policies such as “Look East” and “Neighbourhood First” should be focused on while the BJP stays as the political party in charge of the Government.

If the concept of self-reliance is being put out because of the high percentage of youth in the country, a significant focus should be made on both education and professional skill training programs for these young minds. While competing with technologically driven countries like China and Japan, 80% of engineering students aren’t employable in India (Aspiring Minds, 2019, pp. 6-7) which then creates a lack of suitable workforce for technological and software entrepreneurs and companies wishing to invest in and export from India.

Finally, further research should also be done on economies such as Japan, South Korea and the Mighty 5 other than India, which are Malaysia, Vietnam, Indonesia for their low-cost labour and high skilled productivity (Council on Competitiveness, 2016, pp. 9 -16) which might seek to become a “China Alternative” or change the global paradigm of international trade.

Reference

Cho, (2007), “A Dual Catastrophe of Protectionism”, Northwestern Journal of International Law and Business.

Dhinakaran, Kesavan (2020), “Exports and Imports Stagnation in India During Covid-19- A Review”, ISSN: 1430-3663 Vol-15.

Elias, (2020), “COVID-19: India’s Trade Related Responses” (available at https://www.mondaq.com/india/operational-impacts-and-strategy/923152/covid-19-india39s-trade-related-responses)

Rajagopalan, (2020), “India’s self-inflicted foreign policy challenges in 2020” (available at https://www.orfonline.org/research/indias-self-inflicted-foreign-policy-challenges-in-2020-59858/)

Shikhare, (2020), “ATMANIRBHAR BHARAT ABHIYAN AND SWADESHI”, DogoRangsang Research Journal, ISSN: : 2347-7180, Vol-10 Issue No. 7

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author (s). They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Jindal Centre for the Global South or its members.