Tanveer Malik

Research Intern at Jindal Centre for the Global South

O.P. Jindal Global University

E-mail: 22jsia-tmalik@jgu.edu.in

Introduction

Since 2017, the Chinese government has started rounding up the Uyghur population of Xinjiang province into secret internment camps. The Uyghurs are a religious minority in China. They are Muslims and have a Turkish ethnicity as compared to the majority of Han Chinese living in China. These internment camps currently hold over a million people (Soliev, 2019). This repression is one of the most “harrowing- and yet most neglected- humanitarian crises in the world today” with China having denied these practices (Samuel, 2019). Though shrouded in secrecy, there have been reports of death and torture within the internment camps. Muslim detainees are forced to memorize and recite Chinese communist propaganda and renounce their religion (Samuel, 2019). This paper examines the historical, political and economic importance of the Xinjiang province for the Communist Party of China (CCP) as the answer to the brutal suppression of the Uyghur population in the Xinjiang province.

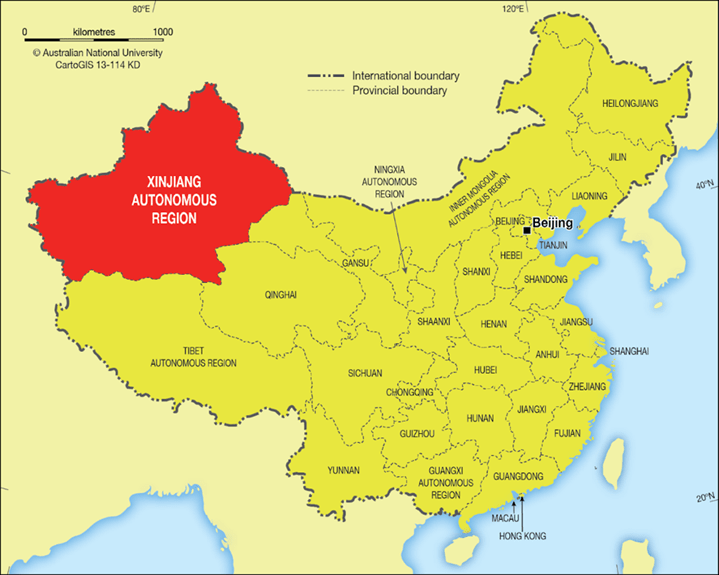

Figure 1

Map of Xinjiang

Historical and Political Importance of the region

China’s colonial experience has proven to be a motivator for its rise on the world stage. Though China was never entirely colonized, it suffered a blow to its territorial integrity at the hand of Western powers and Japan (Dittmer, 2018). This period of Chinese history is dubbed as the “century of humiliation” or “bainan guochi” (Dittmer, 2018). A part of Chinese foreign policy is based around regaining sovereignty over the area, China claims it lost during this period. One of these regions is the present-day province of Xinjiang. The CCP bases its claim on Xinjiang, on the conquest of the region by the Qing dynasty in the 17th century (Clarke, 2013). The Cold War further added to the need for controlling the region. In the early stages of the Cold War, relations with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) were cordial. However, relations soured during the 1970s. China shared an important border with the USSR through the Xinjiang province. The fall of the Soviet Union at the end of the Cold War created insecurity regarding similar separatist movements in the Xinjiang province (Zhao, 2010). This increased the importance to secure the region. In the aftermath of 9/11 attacks, the Uyghur population itself was seen as a threat to the territorial integrity of Xinjiang. The CCP feared Islamic radicalization as a possible catalyst for separatist movements in the province (Tukmadiyeva, 2013). Pushback from the Uyghurs like the 2009 July ethnic riots at Urumqi which led to the death of many Han Chinese in Xinjiang has also prompted further crackdowns on the region. In this way, the province acts as a buffer (Kirby, 2020).

Economic Importance

The province is essential for China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The Belt and Road Initiative is regarded as key to China’s plan of economic and political dominance in Asia and the Global South as a whole. The province connects China, Central Asian countries and Europe through various overland road and railway transportation networks. To that end, China has invested heavily in various countries for the development of this mass connective infrastructure. The project is seen as having the potential to boost free trade immensely and is seen to be especially advantageous for China (Mobley, 2019). Due to the geographic connectivity importance of the province, there has been much investment in the region for BRI. Safeguarding this investment is a top priority for the Chinese leadership. One instance is the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). CPEC as part of BRI seeks to connect directly to the Chinese-controlled Gwadar Port in Pakistan, which is located near the Strait of Hormuz. The Strait of Hormuz is an essential waterway for the supply of crude oil to the world. Through Gwadar Port, China seeks to increase the speed and efficiency of its crude oil supply by bypassing the South China Sea and Southeast Asian countries (Mobley, 2019). In addition, the province is also home to a considerable number of oil and natural gas resources.

Figure 2

BRI Map

Control and Oppression in the Province

The CCP has been gradually encouraging the majority Han Chinese population to move into Xinjiang. This is also accompanied by a suppression of public celebration of various Islamic holidays and even the public reading of the Quran. The residents are also expected to speak Mandarin instead of their language. This has led to incidents of pushback and conflict with the Uyghur population like the 2009 Urumqi riots which led to the death of 200 Han Chinese residents of the city (Kirby, 2020). Uyghur separatists, who were able to escape Xinjiang have joined Islamic militant organizations like ISIS in Syria. A 2017 news report claimed that over 5000 Uyghurs have travelled to Syria to rain with fundamentalists (Shih, 2017). This has further increased state surveillance and state oppression. In 1949, the Han population in Xinjiang constituted only 6 per cent of the total population. The Uyghur population made up 70 per cent of the total population of Xinjiang. Today over 49 per cent of the population is Han Chinese (Luthi, 2013). Over a million Uyghurs have been detained in Chinese re-education centres. In these centres, detainees undergo indoctrination like reading Communist propaganda and giving thanks to the leaders of the CCP. Torture has also been utilized as a tool of indoctrination. Outside these camps, daily life goes on in a state of mass surveillance. Regular security checkpoints at markets and other public places require frequent scanning of identification cards. Facial Recognition Technology is also utilized along with the mandatory collection of blood and DNA samples. Passports of residents have been confiscated and their movement is quite restricted. Other “de-extremification” techniques like banning long beards, ban on Muslim names for children and promoting drinking and smoking in public are encouraged. Moreover, the Uyghur population has also been used in forced labour. Factories of Chinese companies as well as many foreign companies are known to employ Uyghurs as forced labour (Kirby, 2020). Over 80,000 Uyghurs have been transferred to various factories around China. These include companies like Adidas, BMW, Bosch, GAP, Lacoste, Nike etc. Many Chinese COVID masks sold in countries like the United States of America come from these factories. (“83 companies linked to Uighur forced labor”, 2020).

Figure 3

Re-education Centers in Xinjiang

Zhang, S. (2019). Satellite imagery of Xinjiang “Re-education Camp” No 89 [Photograph]. Medium.

Actions taken by the International Community and Suggestions

One of the most recent actions taken by the international community has been a joint statement by G7 countries. On October 22, 2021, the USA, Japan, Germany, Italy, France, the UK, and Canada reaffirmed their commitment to act on “forced labour in global supply chains, including state-sponsored forced labour of vulnerable groups and minorities, including in the agricultural, solar and garment sectors.” Moreover, on October 21st, 2021, 43 countries gave a joint statement at the UN Third Committee, expressing concern for the Uyghur situation. (“International Responses to the Uyghur Crisis”). However mere statements and declarations are not enough. International pressure needs to be put on the PRC to address the issue. Government investigations should be conducted into the labour practices of the companies relying on Uyghur forced labour. Sanctions on these companies, especially Chinese companies, and or barriers to their operation capabilities should also be levied to reduce the instances of forced labour. China’s dominance on the world forum also needs to be countered to put pressure on China to take measures like the admittance of UN investigators into Xinjiang. One method may be increasing the participation of countries opposing China in international organisations like the United Nations Security Council. Countries like India are in a position to counter China’s regional dominance in Asia and force accountability and action. India might accomplish this by reinvigorating its alliances with its neighbours through regional forums like SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation).

Conclusion

The historical, political, and economic importance of the Xinjiang province is one of the key reasons behind the suppression of the Uyghur population. The failure of social cohesion and the cyclical ethnic violence has added to the rising tensions between the Uyghur population and the Chinese government. However, the secret internment camps are a blatant human rights violation. Much of China’s future economic and political dominance in the Global South will be based on a major humanitarian crisis. Though the Chinese government has denied the existence of these camps and has labelled them as vocational education camps, more international attention is paramount to bring this issue to light.

References

Clarke, M. (2013). Ethnic Separatism in the People’s Republic of China History, Causes and Contemporary Challenges. European Journal of East Asian Studies, 12(1), 109–133. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23615293

Dittmer, L. (2018). China’s Asia: Triangular Dynamics since the World War. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

“International Responses to the Uyghur Crisis”. (n.d.). Uyghur Human Rights Project. Retrieved from https://uhrp.org/responses/

Joniak-Lüthi, A. (2013). Han Migration to Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region: Between State Schemes and Migrants’ Strategies. Zeitschrift Für Ethnologie, 138(2), 155–174. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24364952

Kirby, J. (2020, September 25). Concentration Camps and Forced Labour: China’s Repression of Uighurs, explained. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2020/7/28/21333345/uighurs-china-internment-camps-forced-labor-xinjiang

Mobley, T. (2019). The Belt and Road Initiative: Insights from China’s Backyard. Strategic Studies Quarterly, 13(3), 52–72. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26760128

Shih, G. (2017, December 23). AP Exclusive: Uighurs fighting in Syria take aim at China. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/syria-ap-top-news-riots-international-news-china-79d6a427b26f4eeab226571956dd256e

Siguel, S. (2019, March 30). China’s crackdown on Muslims is being felt beyond its borders. Vox. https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2019/3/30/18287532/china-uighur-muslims-internment-camps-turkey

Soliev, N. (2019). UYGHUR VIOLENCE AND JIHADISM IN CHINA AND BEYOND. Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses, 11(1), 71–75.

Sound Vision (2020, March 10). 83 companies linked to Uyghur Forced Labour. Save Uyghur. https://www.saveuighur.org/83-companies-linked-to-uighur-forced-labor/

Tukmadiyeva, M. (2013). Xinjiang in China’s Foreign Policy toward Central Asia. Connections, 12(3), 87–108. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26326333

Zhao, T. (2010). Social Cohesion and Islamic Radicalization: Implications from the Uighur Insurgency. Journal of Strategic Security, 3(3), 39–52. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26463144

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author (s). They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Jindal Centre for the Global South or its members.