Tejas Vir Singh

Research Intern at Jindal Centre for the Global South

O.P. Jindal Global University

E-mail: 21jgls-tvsingh@jgu.edu.in

Introduction

This article will dwell into the problem of green neocolonialism that has arisen in today’s fragile situation of climate change and the efforts needed to minimize its effects. The term ‘neocolonialism’ came into usage in order to shed light on the Global North’s attitude towards the Global South when it comes to policy implementation and profit maximization at the cost of environmental stability. The article will also discuss various instances of green colonialism in Africa and the debate that has arisen regarding it.

Neocolonialism turns Green

Neocolonialism was first termed by Jean-Paul Sartre, a French philosopher, in 1956, and was used by Kwame Nkrumah in the African context during the decolonization of Africa in the 1960’s. It refers to a form of power position that a country, usually a former colonial power, tends to hold over another, weaker state, in a near-imperialist way, usually to control the country in a cultural or economic context. There are multiple types of neocolonialism, namely economic imperialism, globalization, cultural imperialism, and conditional aid that leads to indirect control of the country by establishing a sort of hegemony.

Eco-Imperialism was termed by Paul Driessen, referring to the imposition of Western views on environmentalism on developing countries in forceful ways (Duquette). It arises from a ‘White Savior Industrial Complex’, a phrase termed by Teju Cole, where the West pretends to care about the ecosystem of the developing world, and instead harms the ecosystem by preservation efforts that were aimed to reverse the damage done by colonial rule (Duquette). This mindset carried by colonialists, rooted in capitalism, leads to green neocolonialism when Western capitalism mixes with a history of environmental colonialism (Knox). The capitalist mindset has led to environment to become a simple commodity that can be exploited for profit, and in today’s postcolonial world, in a way that avoids the blame from falling on the West while they gain the profit.

In Africa, green neocolonialism largely revolves around oil, such as in Democratic Republic of the Congo and Nigeria.

Deforestation for fuel in Democratic Republic of Congo.

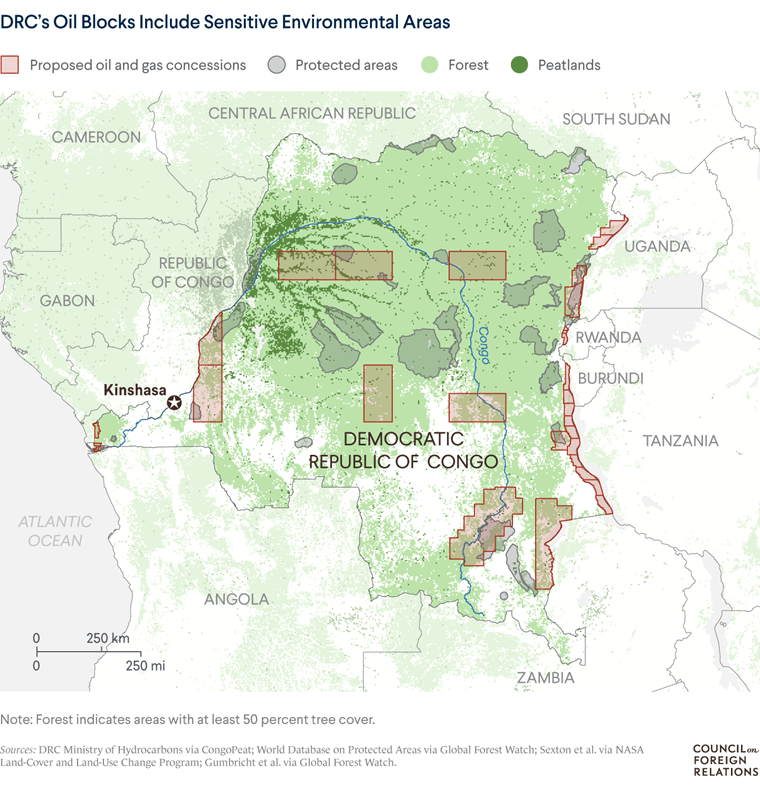

The Democratic Republic of Congo’s government decided to auction off 27 oil blocks and 3 gas blocks to whoever bid the highest for these lands to exploit its natural resources and profit by selling the raw material and resources that DRC has in abundance (Tsafack, 2022). The government proudly claims it is an act against neocolonialism and a move of nationalism, with the minister of communications stating “we care more for human being than gorillas,” (Tsafack, 2022). This instead fuels neocolonialism by mirroring the ‘Scramble for Africa’ of the nineteenth century and gives European countries more power than the Congolese government to control its domestic resources. Moreover, those who live on these auctioned lands were not informed of such a change that will uproot their livelihoods, after officials of Greenpeace Africa asked the locals about this policy (Tsafack, 2022).

The DRC remains one of the poorest countries in the world, despite being immensely rich in resources. Mass corruption and instability in the country for decades seems to have fueled a need for quick profit attained by selling off resources to the Global North such as European countries looking for alternative sources of petroleum instead of relying on Russia (Tsafack, 2022). This strategy of selling off resources has done barely anything for DRC, a nation that Tsafack (2022) describes as being infamous for its corruption and poverty, child labour and hardships in mines.

Source: Council for Foreign Relations

Colonial Oil and Nigeria

Nigeria’s colonial history is heavily influenced by oil. British companies like Shell-BP, set up a system of oil extraction in Nigeria that catered to the needs of the colonial masters and foreign companies that gained immense profit through the heavy concessions made by the British in Nigeria, giving them complete control of the region’s natural resources (Wells, 2019). In Nigeria and Equatorial Guinea, the economies remain as highly dependent on oil as they were when oil production was first started. In 1976, oil accounted for 90% of Nigeria’s forex earnings and half of its GDP, and even today, the statistics are similar (Wells, 2019). In fact, oil production has increased over the decades, but the per capita income has fallen, widening the gap between the two (Uwakonye et al., 2006, p. 72.); Uwakonye (2006) suggests that the profits gained from oil production are going to anyone but the Nigerian people.

Where is this money going?

Even though the oil industry is nationalized in Nigeria, the actual resource lies in the hands of foreign companies that hold huge influence over the government. Oil may be nationalized, but the power over it lies in foreign hands, and not that of Nigeria. Foreign companies like ExxonMobil, Royal/Dutch Shell, and BP are some of the multinational oil companies that have influence in Nigeria and gain almost half of all profits of Nigeria (Uwakonye et al., 2006, p. 61). This also means that local contractors are omitted from making these profits, and that a small population is employed in profitable industries (Uwakonye et al., 2006, p. 61). This references not only to the Western dominated oil sector but other sectors such as infrastructure, which is dominated by new neocolonialists such as China, who utilize their own workforce in African countries who send their earnings back home, while Africans are denied a chance to gain employment (Wells, 2019). This sector also is responsible for health effects such as bronchial, chest and eye problems caused by gas flaring in the Niger Delta (NPR, 2007).

Thus, like in the case of DRC, the power over such an important resource is handed over to neocolonial masters who gain all the profit at the cost of the locals.

Source: Uwakonye et al., 2006, p. 72.

Neocolonialism vs Post-colonialism

The companies of the West are not the only ones profiting from Africa’s raw resources. Guillaume Blanc, an environmental historian, argues that African leaders also play a role in the degradation of the environment, as they actively perpetuate colonial traditions to gain advantage for themselves (Sustainable Development News, 2021), by collaborating with these foreign companies. Blanc argues that the colonial mindset and narrative has entrenched the idea of a ‘virgin’ Africa in our minds, that before the arrival of the Europeans it was a land ruled by wildlife, and the savanna had been formed by the destruction of the large forest by local populations, and that this narrative of the locals being at fault has persisted since then (Sustainable Development News, 2021); he cites the example of UN experts stating the disappearance of forests in Sierra Leone and Guinea, while in fact they have become greener than before (Sustainable Development News, 2021). Thus, it is also possible to say that green neocolonialism also exists in narratives, as to who is designated as the ’perpetrator’ and who the ‘savior’.

Moreover, the continuation of colonial policies is also worrying. An example is that of the nature parks, that were once hunting reserves for the colonialists, who blamed the widespread destruction of forests and wildlife during colonial rule on the local populace; in less than a century, 95 million hectares of forest in Africa and Asia were cleared (Ross, 2017). These hunting reserves went on to become national parks during decolonization, and the people living and/or displaced from these parks became ‘criminals’ that are subject to brutality by eco-guards equipped with weapons, originally placed there to prevent poaching, such as in Botswana where a hunting ban led to killing of civilians by rangers not only of Botswana, but also neighbouring Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe (Somerville, 2018). These parks thus become a site of violence on civilians in order to protect the environment, for the thinking that Africans degrade the environment and Europeans shape it, has become so engrained.

Conclusion

Colonialism may have ended, but the problem of neocolonialism has arisen, where many of these former colonial powers still hold sway over their former colonies. This can be seen in the instance of environment and sustainability, termed as ‘green’ neocolonialism, where countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo are more than willing to give up their forests and the livelihoods of its civilians in order to earn profit from the Western companies that will be given the power to extract resources such as oil and gas for themselves, and in Nigeria where due to colonial practices, the Western companies get half the revenue of what the country produces from its oil production, leaving barely anything for the local population. Moreover, this neocolonialism exists in narratives too, designating a perpetrator and savior in environmental degradation.

The narrative needs to change, and the voice of the decolonized needs to be heard. Although there is increasing awareness of environmental degradation and the need for sustainability in this day and age, neocolonialism, particularly green neocolonialism inhibits the ability of those affected or most susceptible to climate change to make a difference, as seen in the case of various African countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Nigeria, where the government tends to prioritize profits over its people. A stronger stance against neocolonialism must be taken by international non-governmental organizations that can openly advocate for the rights of the decolonized peoples. Moreover, it is also the duty of the citizens of the Global North to recognize and put a check to their privileges that they gain by reducing access and opportunities of those living in the Global South.

Reference

Duquette, K. (2019, January). Environmental Colonialism. https://scholarblogs.emory.edu/postcolonialstudies/2020/01/21/environmental-colonialism/#:~:text=Environmental%20colonialism%20refers%20to%20the,able%20to%20alter%20native%20ecosystems.

Knox, A. (2021, May 16). Capitalism and the Green Agenda: A Green New Deal or Green Neo-Colonialism?. https://www.humanrightspulse.com/mastercontentblog/capitalism-and-the-green-agenda-a-green-new-deal-or-green-neo-colonialism

Neocolonialism. In Wikipedia. (2022, December 19).https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neocolonialism

NPR. (2007, July 24). Gas Flaring Disrupts Life in Oil-Producing Niger Delta. https://www.npr.org/2007/07/24/12175714/gas-flaring-disrupts-life-in-oil-producing-niger-delta

Ross, C. (2017). Ecology and Power in the Age of Empire: Europe and the Transformation of the Tropical World. Oxford University Press.

Somerville, K. (2018, August 20). Militarization of conservation: an army of occupation, not protection. https://global-geneva.com/militarization-of-conservation-an-army-of-occupation-not-protection/

Sustainable Development News. (2021, January 07). “Green colonialism”: the background behind a Western outlook on African nature. https://ideas4development.org/en/green-colonialism-western-outlook/

Tsafack, M.A.F. (2022, August 18). DRC’s forests-for-oil sale reeks of neocolonialism. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2022/8/18/drcs-forests-for-oil-sale-reeks-of-neocolonialism.

Uwakonye, M.N., Osho, G.S. & Anucha, H. (2006). The Impact of Oil and Gase Production On The Nigerian Economiy: A Rural Sector Econometric Model. International Business & Economics Research Journal, 5(2), 61-76.

Wells, A. (2019, April 18). Neo-colonialism Fuels Your Car. https://brownpoliticalreview.org/2019/04/neo-colonialism-fueling-car/

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author (s). They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of the Jindal Centre for the Global South or its members.

Disseminating this article can create awareness regarding green neo colonialism that inhibits the ability of those affected or most susceptible to climate change to make a difference, as seen in the case of various African countries.

Well projected topic Tejas !!

LikeLike